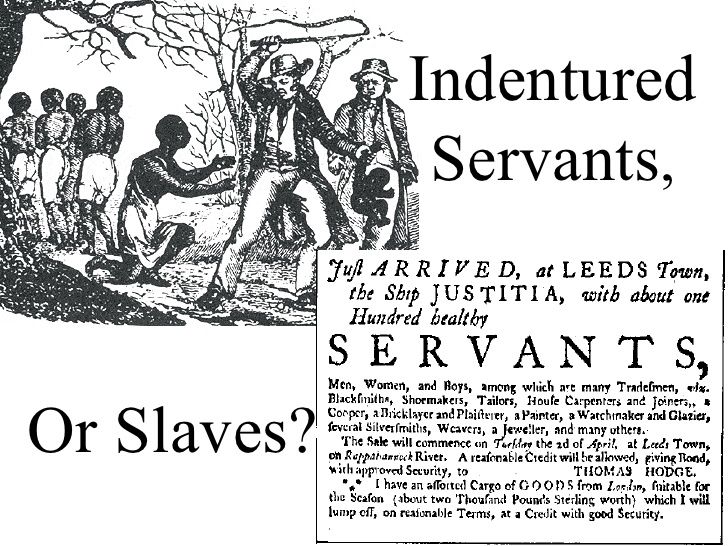

Why Europeans (often called “white” in older usage) came as indentured servants

Push and Pull Factors

Why Europeans (often called “white” in older usage) came as indentured servants

Push and Pull Factors

-

Economic hardship / lack of land in Europe — Many poor Europeans (Irish, English, Scots, Germans, etc.) had limited prospects at home: poverty, famine, lack of inheritance, overpopulation of rural areas, etc.

-

Promises / incentives in the colonies — The New World was advertised (in pamphlets, by agents) as a land of opportunity: land, wages, and better conditions could be had.

-

Cost of passage — Many could not afford the transatlantic voyage. So many entered into indenture contracts: someone paid their passage, and in return they agreed to work for a fixed number of years (commonly 4–7 years) for that sponsor or in that colony.

-

Coercion, deception, debt bondage — In practice, many were tricked, misled, or forced into contracts, or had their contracts extended by penal clauses. The conditions could be brutal (long work days, harsh treatment, poor living conditions, sickness, even death).

-

Legal status during the contract — While under contract, their mobility, rights, and freedom were restricted. They might be bought, sold, or have time extended for “infractions.”

So while these individuals were not enslaved in the same legal, hereditary sense as African chattel slavery, their experience sometimes had severe elements of coercion, exploitation, and limited freedom.

Over time, especially in the 17th–18th centuries, indentured servitude declined (in part because slave labor became more profitable, mortality rates improved, and labor economics shifted).

Naturalization / Citizenship Laws: How “white immigrants” were treated in law, and how long until they could become citizens

Because you mentioned “white” people and bills allowing them to stay / become citizens, here is the legal evolution:

The constitutional authority & early naturalization

-

The U.S. Constitution gives Congress the power to establish “uniform rules of naturalization.” Legal Information Institute+2Wikipedia+2

-

The first national (federal) law was the Naturalization Act of 1790 (March 26, 1790). migrationpolicy.org+3George Washington’s Mount Vernon+3The American Leader+3

-

It stated that “any alien being a free white person, who shall have resided within … for the term of two years … may be admitted to become a citizen” (with additional requirement of one year in the state). George Washington’s Mount Vernon+2The American Leader+2

-

It also included that children under 21 of such naturalizing persons (if they live in the U.S.) would be naturalized along with them. George Washington’s Mount Vernon+1

-

It explicitly excluded indentured servants, slaves, and non-whites (i.e., only “free white persons” could naturalize) in practice. Densho Encyclopedia+3Cato Institute+3The American Leader+3

-

-

In 1795 the Naturalization Act was revised:

-

It increased the necessary residence from 2 to 5 years. Wikipedia+2George Washington’s Mount Vernon+2

-

It introduced a “declaration of intention” (sometimes called first papers) to be filed at least 3 years before the application. Wikipedia+2George Washington’s Mount Vernon+2

-

It kept the same “free white person” limitation. Cato Institute+3Wikipedia+3UC Davis Law Review+3

-

-

In 1798, under the Alien and Sedition Acts, the residency requirement was pushed even further:

-

It increased the required residency to 14 years and extended the “notice / declaration of intention” requirement to 5 years. Wikipedia+2migrationpolicy.org+2

-

This was seen as a politically motivated move to limit the number of new citizens (especially for newcomers who might vote against the existing ruling party). Shec+3Wikipedia+3American Reformer+3

-

-

In 1802, Congress rolled back the 1798 law:

-

It restored the 5-year residence requirement and the 3-year notice requirement. Wikipedia+2George Washington’s Mount Vernon+2

-

Still the “free white person” limitation remained. Wikipedia+2Cato Institute+2

-

-

Over the 19th century, there were additional changes:

-

In 1870, the Naturalization Act of 1870 extended naturalization to “aliens of African nativity and persons of African descent.” That is, free blacks immigrating (not enslaved) could now become citizens. migrationpolicy.org+3Wikipedia+3Cato Institute+3

-

But other racial groups (for example, many Asian immigrants) were still excluded under other laws. USCIS+2Cato Institute+2

-

-

In 1906, the Basic Naturalization Act of 1906 standardized and centralized the naturalization process:

-

It created a federal agency (Naturalization Service) to oversee naturalization and required standard forms. USCIS+2National Archives+2

-

It required that applicants speak English. USU Library Guides+1

-

It set uniform rules nationwide so that all courts followed the same processes. USCIS+2National Archives+2

-

-

Later, the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) of 1952 (and subsequent amendments) consolidated and reformed immigration and naturalization laws into one code. USCIS+2Wikipedia+2

-

Importantly: the “free white person” clause was eliminated in 1952 as part of the reforms to the law. (That is, the racial exclusion was formally dropped.) UC Davis Law Review+3W&M Law School Scholarship Repository+3USCIS+3

How long it took for someone to become a citizen (under “white immigrant” rules)

Putting that together:

-

Under the 1790 Act, one needed 2 years in the U.S. plus at least 1 year in the state before applying. George Washington’s Mount Vernon+2The American Leader+2

-

Under the 1795 Act, it was extended: 5 years residence + at least 1 year in the state + the declaration of intention requirement (3 years in advance) before formal application. Wikipedia+2George Washington’s Mount Vernon+2

-

Under the 1798 Act, it was 14 years residence + 5 years’ notice before applying. Wikipedia+2migrationpolicy.org+2

-

Under the 1802 Act, it went back to 5 years + 3 years notice. Wikipedia+2George Washington’s Mount Vernon+2

-

After that, changes were more about administration, race inclusion, and process standardization than radical changes in residency time (though some specific immigrants under special laws might have different paths).

So for a “white immigrant” under early U.S. law, in many cases the path to citizenship took about 5 years (under the 1795 and post-1802 regimes), though in some narrow windows it was 2 years or, under 1798, 14 years.

Bills / Congressional acts to “let them stay” / arguments

I’m not aware of a specific bill solely for “white indentured servants” to stay permanently; rather, the naturalization / immigration laws overall governed who could stay, become citizens, and vote. Some relevant points:

-

The Naturalization Acts themselves were congressional bills that authorized certain immigrants to become citizens under certain conditions (as described above).

-

Some Congresses and state legislatures debated whether recent immigrants should be admitted earlier or later, especially when political factions (Federalists vs. Democratic-Republicans) clashed. For example, the 1798 Act is often seen as motivated by politics (limiting citizenship to preserve power). Cato Institute+3Wikipedia+3American Reformer+3

-

Over time, as the U.S. expanded and immigration grew, debates over quotas, exclusion laws, and eligibility occurred (especially in the late 19th and early 20th centuries).

-

The Naturalization Act of 1870 was a significant step by Congress to extend citizenship rights to “aliens of African nativity and persons of African descent.” That shows that Congress itself had to act to expand the classes of people eligible. Wikipedia+2UC Davis Law Review+2

-

Later, naturalization reforms like the 1906 Act were also congressional — standardizing, centralizing, setting English requirement, oversight, etc. USCIS+2USU Library Guides+2

If you come across a specific bill you read (for example, a Republican-led bill to expand immigrant naturalization), I can help you locate it in congressional records.

Issues, criticisms, and framing

-

Selective memory / erasure — Many mainstream narratives emphasize the African slave trade and its horrors (rightly so), but often marginalize or ignore that European indentured laborers also faced harsh conditions, fraud, and limited freedom. Including their stories does not justify or diminish the unique, brutal system of race-based chattel slavery, but enriches the fuller picture of labor, coercion, and migration.

-

Difference in legal status and duration — Indentured service was time-limited; after the term, an individual could (often) gain land, freedom, or wage labor. African chattel slavery was typically lifelong (unless freed) and hereditary. So you need to draw clear distinctions in your article so readers don’t conflate them.

-

Political motives in lawmaking — Many amendments (like 1798) were less about justice and more about maintaining political power (e.g. limiting who could vote, controlling new immigrant influence). Also racial exclusions in the Naturalization Acts reflect how “whiteness” was legally constructed and privileged. USCIS+3W&M Law School Scholarship Repository+3UC Davis Law Review+3

-

“Free white persons” clause legacy — That phrase in early law helped enshrine racial boundaries around U.S. citizenship and whiteness. Its removal (in 1952) was a slow and contested process in American legal history. USCIS+3W&M Law School Scholarship Repository+3USU Library Guides+3