The Origins of the NAACP: Allies, Money, and the Struggle for Civil Rights

The Origins of the NAACP: Allies, Money, and the Struggle for Civil Rights

By Erika Trenell | Nativa Party Historical Series

A Call for Justice

In 1908, the city of Springfield, Illinois erupted in racial violence. Two Black men were lynched, dozens of homes were burned, and the shock reached national headlines.

Out of that tragedy came a group of reformers — Black and white — who believed the time had come for a permanent organization to defend African-Americans’ rights.

On February 12, 1909, exactly 100 years after Abraham Lincoln’s birth, they issued a public “Call” for civil and political liberty.

That call led to the founding of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People — the NAACP.

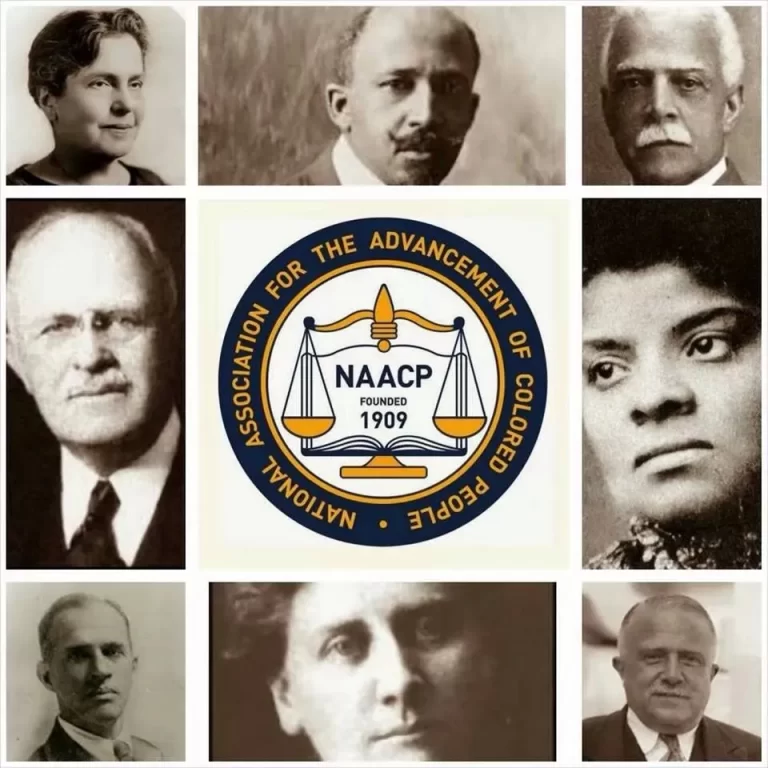

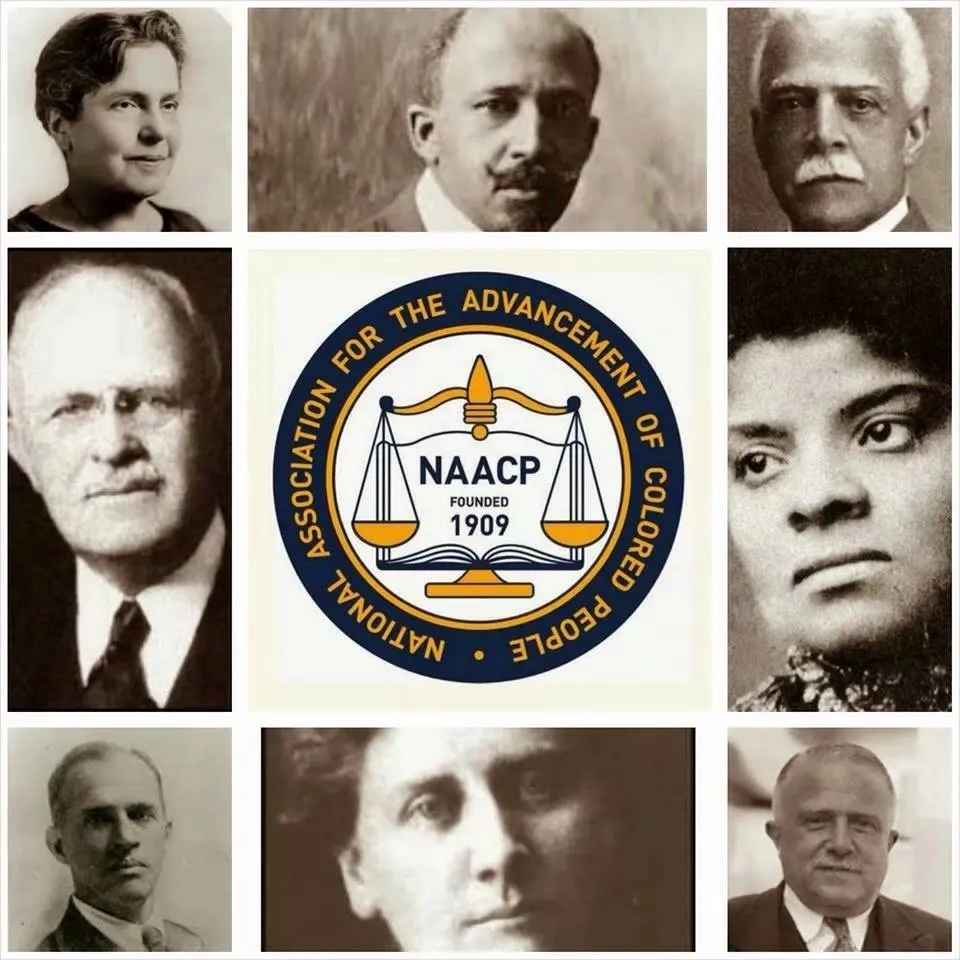

The Founding Circle

The founding group included:

W.E.B. Du Bois – sociologist, scholar, and editor of The Crisis magazine, the NAACP’s first major publication.

Ida B. Wells-Barnett – anti-lynching journalist from Memphis whose investigations exposed racial terror.

Mary White Ovington – white social worker and suffragist who helped organize the first planning meeting.

William English Walling – wealthy Southern socialist who wrote the essay “Race War in the North”, which inspired the original call.

Henry Moskowitz – Jewish civil-rights activist from New York who connected early funders and networks.

Oswald Garrison Villard – newspaper publisher and grandson of abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison.

At the time, it was rare — almost unheard of — for Black and white reformers to work together publicly, but this interracial alliance became the NAACP’s foundation.

Who Funded the NAACP

Because most Black Americans were still struggling under Jim Crow oppression and economic hardship, the early NAACP relied heavily on progressive white and Jewish donors for its first offices, publications, and legal campaigns.

Among them were:

Jacob Schiff, a German-Jewish banker and philanthropist who financed anti-lynching efforts and early organizational costs.

Joel Spingarn and his brother Arthur Spingarn, who later served as NAACP presidents and contributed large personal sums.

Mary White Ovington and William Walling, who both came from affluent families and donated heavily.

Their financial backing made the NAACP a powerful lobbying and legal organization when few others had the resources to operate nationally.

While this support was essential, it also shaped the organization’s tone: cautious, legalistic, and oriented toward gradual reform through the courts.

The Mission and the Method

The NAACP’s motto became “To ensure the political, educational, social, and economic equality of rights of all persons and to eliminate race-based discrimination.”

Its early victories came through:

Public awareness campaigns – exposing lynchings and segregation.

Legal challenges – culminating in cases like Brown v. Board of Education decades later.

The Crisis Magazine – edited by Du Bois, which spread news of Black achievement and protest across the world.

Criticism from Within the Race

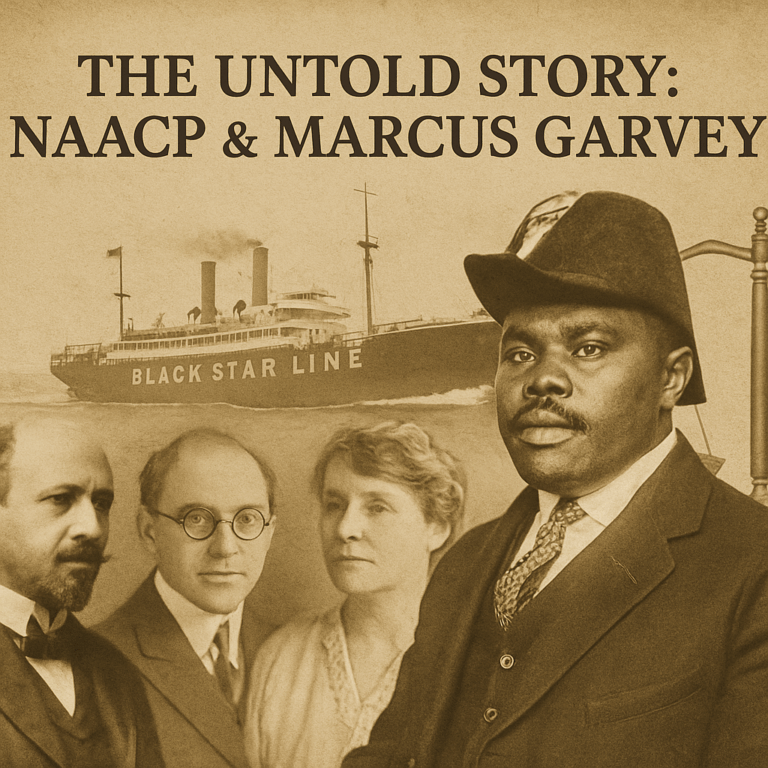

Not all Black leaders supported the NAACP’s integrationist path.

Marcus Garvey, A. Philip Randolph, and others criticized it for being too dependent on white money and for failing to promote Black-owned enterprise.

Garvey, in particular, saw the NAACP’s white-funded structure as a sign that true freedom could not be achieved under financial control from outside the community.

Despite those critiques, the NAACP persisted — and in time, it grew more self-sufficient as a new generation of Black lawyers, organizers, and donors emerged.

Legacy and Lasting Impact

By the 1950s and 1960s, under leaders like Thurgood Marshall and Roy Wilkins, the NAACP became the legal backbone of the Civil Rights Movement, winning landmark cases that dismantled school segregation and voter suppression.

What began as an interracial coalition in 1909 evolved into a fully Black-led civil-rights institution that still operates today.